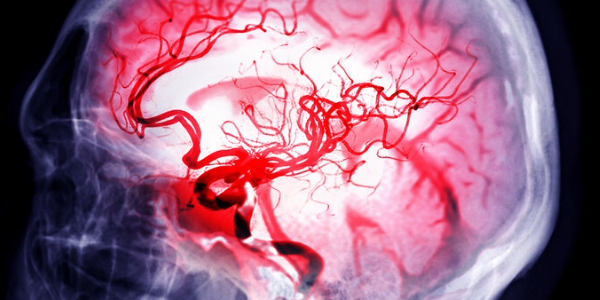

Stem cell transplants can reverse stroke damage, according to researchers at the University of Zurich. The positive effects include the regeneration of neurons and the restoration of motor functions, which represents a milestone in the treatment of brain diseases. One in four adults suffers a stroke during their lifetime, and more than 80 percent of all stroke patients are over 60 years of age.

Ewa Half of those affected suffer permanent damage such as paralysis or speech disorders, as internal bleeding or oxygen deprivation irreversibly destroy brain cells. There are currently no therapies available to repair such damage. “That’s why it’s essential to pursue new therapeutic approaches for the possible regeneration of the brain after illness or accidents,” says Christian Tackenberg, scientific director of the Neurodegeneration Department at the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Zurich (UZH). Neural stem cells have the potential to regenerate brain tissue, as a team led by Tackenberg and postdoctoral researcher Rebecca Weber has now convincingly demonstrated in two studies conducted in collaboration with a group led by Ruslan Rust from the University of Southern California. “Our results show that neural stem cells not only form new neurons, but also induce other regeneration processes,” says Tackenberg.

New Neurons from Stem Cells

The studies used human neural stem cells, from which various cell types of the nervous system can form. The stem cells were obtained from induced pluripotent stem cells, which in turn can be produced from normal human body cells. For their study, the researchers induced a permanent stroke in mice, the characteristics of which are very similar to those of a stroke in humans. The animals were genetically modified so that they would not reject the human stem cells.

One week after inducing the stroke, the research team transplanted neural stem cells into the injured brain region and observed the subsequent developments using various imaging and biochemical methods. The researchers found that the stem cells survived throughout the five-week analysis period and that most of them transformed into neurons that even communicated with the existing brain cells.

The researchers also found other signs of regeneration: the formation of new blood vessels, a reduction in inflammatory processes, and improved integrity of the blood-brain barrier. “Our analysis goes far beyond the scope of other studies, which focused on the immediate effects immediately after transplantation,” explains Tackenberg. Fortunately, stem cell transplantation in mice also reversed the motor impairments caused by the stroke. This was demonstrated, among other things, by an AI-assisted gait analysis of the mice.

Clinical Application is Getting Closer

When designing the studies, Tackenberg already had clinical applications in humans in mind. For this reason, the stem cells were produced without the use of animal reagents, for example. To this end, the Zurich research team developed a defined protocol in collaboration with the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Kyoto University. This is important for potential therapeutic applications in humans. Another new finding was that stem cell transplantation works better when it is performed one week after a stroke rather than immediately after, as confirmed by the second study. In a clinical setting, this time window could greatly facilitate the preparation and implementation of the therapy.

Despite the encouraging results of the studies, Tackenberg warns that much work remains to be done. “We need to minimize the risks and simplify potential applications in humans,” he says. Tackenberg’s group is currently working again with Ruslan Rust on a kind of safety switch that prevents uncontrolled growth of stem cells in the brain. The administration of stem cells by endovascular injection, which would be much more practical than a brain transplant, is also under development. According to Tackenberg, initial clinical trials for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease in humans using induced stem cells are already underway in Japan. Stroke could be one of the next diseases for which a clinical trial becomes possible.